The Allen brothers: To the snide, the sweaty, the curmudgeonly disgruntled, .they were the pair of slick New York land speculators who, hot on the heels of the 1836 victory at San Jacinto, trumped up a godforsaken, pestilential swamp into the Texian promised land.

No place in the new republic was healthier than Houston, they crowed, “having an abundance of excellent spring water and enjoying the sea breeze in all its freshness. … It is handsome and beautifully elevated, salubrious and well-watered.”

You can almost hear Augustus Chapman and John Kirby — condemned by popular imagination to the only spot hotter than H-town in August — snickering now.

On the occasion of the city’s 175th anniversary, maybe the time has come to give the brothers an even break, Were their promotional claims really all that outrageous? Here we are, after all, still on the bayou, fat and sassy.

First, the basics.

Worldly and eager

By the time they landed in the East Texas hamlet of San Augustine in 1832, Augustus, born in 1806, and younger brother John, born four years 4ater, already had amassed formidable savvy in the ways of the world.

Augustus had labored as a mathematics professor, bookkeeper and part owner

of a New York City business that also employed his brother. John, launching his career at age 7 as a hotel callboy, had clerked and run a hat shop in partnership with a friend. Augustus, small in stature, was described as “taciturn and settled;” his brother, ‘bright” and “quick.”

Down payment on future

Their second year in Texas found them in Nacogdoches, engaged in the feverish land business. With the revolution’s eruption in 1836, the Aliens eschewed combat but launched — at their own expense — a ship to protect the Texas coast and transport

troops and supplies. The brothers also raised loans and — without taking a cut — served as conduits for supplies and money.

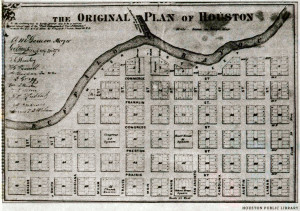

San Jacinto’s smoke hardly had cleared before the incipient city-builders were back to wheeling and dealing. After a few false starts — at one time they considered the burned-out town of Harrisburg — the brothers settled on a site for their town at the confluence of Buffalo and White Oak bayous.

Using money from Augustus’ wife’s inheritance for the down payment, the brothers bought a league and a half of land for $5,000. “The town of Houston is located at a point on the river which must ever command the trade of the largest and richest portion of Texas .“ they proclaimed in an Aug. 30, 1836, newspaper advertisement.

Further, they predicted, their new town — craftily named to appeal to the republic’s future president’s vanity — would become “beyond all doubt, the great interior commercial emporium of Texas.”

Free capitol, cheap rent

In September 1836, John Allen was elected to the republic’s congress. One month later, he was promising a free capitol and cheap rent for other buildings if the fledgling nation would move its government to the new tent city. Lawmakers left their temporary capital in Columbus for Houston in May 1837.

While the Allen brothers were subject to grandiose visions and given to making unsubstantiated claims, their choice of Houston’s location was not unwarranted. Historian David McComb observes the town was well-situated for water transportation — an invaluable resource in the pre-railroad era.

Though oyster reefs and sandbars made Galveston Bay treacherous, Buffalo Bayou — from Allen’s Landing at Main Street’s foot to the bay — offered consistently deep water. The town itself was, as the brothers contended, centrally situated among fledgling settlements so as to serve as a market center.

Galveston — just an eight-hour steamboat ride, the brothers claimed, from Houston — was deemed one of the western Gulf of Mexico’s premier ports.

As the town grew, not only as a market center but as a center for shootings, knifings and gougings, the Allens offered $1,000 to the captain of the steamer Laura M. to prove how easily the bayou could be traversed. Unfortunately, intoxicated by the beauty of the bayou-side vistas, the boat’s crew passed the Houston wharf, not recognizing their error until they became entangled in bayou vines three miles above town. The journey’s final Harrisburg-to-Houston leg, a 16-mile distance, took three days to complete, but the captain claimed his prize.

Yellow Fever

Despite the town’s rough edges, Sam Houston loved his namesake village, proclaiming it “far superior” to other contenders as a seat of commerce and government.

John Allen never lived to see his city blossom. He died in August 1838 of “congestive fever” and was buried in Founders Memorial Cemetery. The next year, 12 percent of the city’s population died in the first of 10 yellow fever epidemics that hit the city in the next three decades. Texas’ congress voted to move the republic’s capital to Austin.

Augustus Allen stayed in Houston until 1850, when —roiled by the issue of tapping his wife’s inheritance — his marriage crumbled. Plagued by failing health, the elder Allen moved to Mexico, where he held consular positions with the U.S. government. Critically ill, he returned to Washington, D.C., where he died on June 11, 1864. He is buried in Brooklyn, N.Y. Greenwood Cemetery.

Call Bill Edge at 713-240-2949 to see Houston Homes in 24 hours or less.

Source: Houston Chronicle August 28, 2011